"They only bite if you're bleeding"

City girl braves anacondas, giant cockroaches, and piranhas in the Peruvian Amazon.

April 10, 2023

“The piranhas… I’ve seen them eat a big deer. It took only ten minutes.”

“So you can’t swim in the river?”

“You can. They only bite if you’re bleeding.”

This makes me uneasy because I am bleeding, heavily, steadily, soaking a giant sanitary pad in a shitty boat on the Amazon River. The water is the color of milky coffee, so you can’t see the life teeming just beneath—thirty species of piranha, three kinds of electric eel, and two varieties of river dolphin, which like to play in the waves of the boat.

They’re pink dolphins, which sounds whimsical, but they’re actually hideous and strangely prehistoric: when they leap I see thick ropes of muscle, bulging foreheads, and long, humanoid penises. According to one myth, they transform into handsome men in white suits who seduce women after dark. You’re not supposed to look them in the eye.

We’re in a steaming swamp fishing for piranha. Later we’ll eat them, even though they’re mostly teeth and bone. I’m hot, stewing in my own blood, and the boat is wobbly, which is my fault. I’m jumpy: The piranha bate—raw meat—is attracting a kind of flesh-eating bee. I hate bees. I hate bugs. Jay laughs at me. “You look funny,” he says, “in those Prada sunglasses.”

Orlando laughs as well. Stout, big-bellied, and pacific, he’s always laughing—at me, at Jay, at our stupid clothes and bug spray. He was born and raised in a village deep in the jungle, a two-week journey from where we are now. He’s going back soon and invites us to join him. “It’s safe,” he says, “if you know what you’re doing.”

Kids in his village learn how to hunt at eleven; by twelve “they should know how to survive.” This was the case for Orlando, who can spear fish from three meters away, identify poisonous fruits and medicinal flowers, and navigate the endless labyrinth of tree and river using only the sun and stars.

Safe! I cry, slapping a bee. What about all of those explorers who died in the Amazon searching for El Dorado? Orlando laughs again. “They didn’t know what they were doing, and—” he unhooks a piranha, showing me its mouth, an awful spiral of Charybdis teeth, “—they were bad people.”

Sure, he’d heard El Dorado lore as a boy. He’d even found gold in the jungle: A pool of sparkling white stones which a jeweler in Iquitos confirmed were full of 24-carat gold. But he never went back to the pool, and he didn’t tell anyone where it was. He didn’t want to see it plundered.

Anyway, he continues, he’s not interested in cities of gold. What he’s searching for is the legendary giant anaconda—100 feet long and as thick as a tree trunk. A few days before, when we’d met, he’d asked me what I wanted to do in the jungle. Leave, I thought. Find the snake, I said. He’d nodded and grinned, flashing gold teeth.

Today he wears a shirt that says: KEEP CALM, YOU’RE JUST HIGH. So, what’s the deal with Ayahuasca? Orlando warns us that most shamans are not legit, especially if you can find them on the internet. He’s taken it once, under the supervision of his village shaman, who instructed him to collect the vine, muddle, brew, and strain the tincture. After letting it sit for three days he drank two ounces as the shaman chanted and blew smoke in his face. His limbs turned “fluorescent” and he fell asleep, whereupon he dreamed of his father, who had just passed away. He woke up after an hour and the shaman fed him fish soup. “It was good,” says Orlando, placidly. “The soup. And seeing my dad. We hunted together.”

Orlando is in love with the jungle, though he’s been stung by scorpions, bitten by snakes, and lost a chunk of his thumb to a piranha. His closest call? Stepping (barefoot) on the neck of a deadly pit viper. He kept his big toe on its jaw while it spat venom until he found a piece of wood big enough to bash its head in.

I think this story is extremely cool, but he doesn’t like killing animals. He only does it to eat. “I think that nature only hurts us if we hurt nature,” he says. I quit swatting at the bees.

The sun goes down and a thick net of white stars settles across the sky. The Milky Way is a pale, smokey band of pink and lilac light. A firefly tumbles into the boat, and it’s like a star has dropped right out of the sky.

***

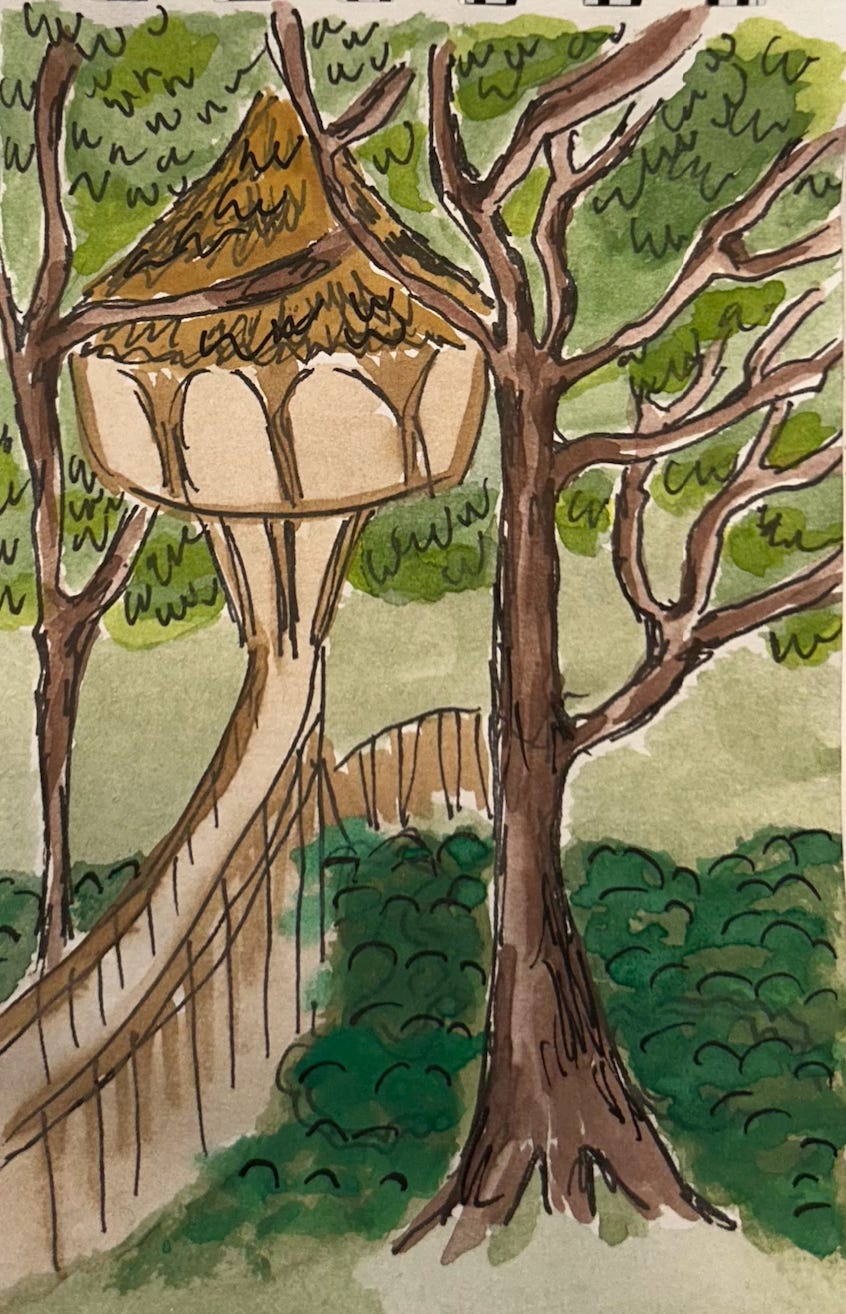

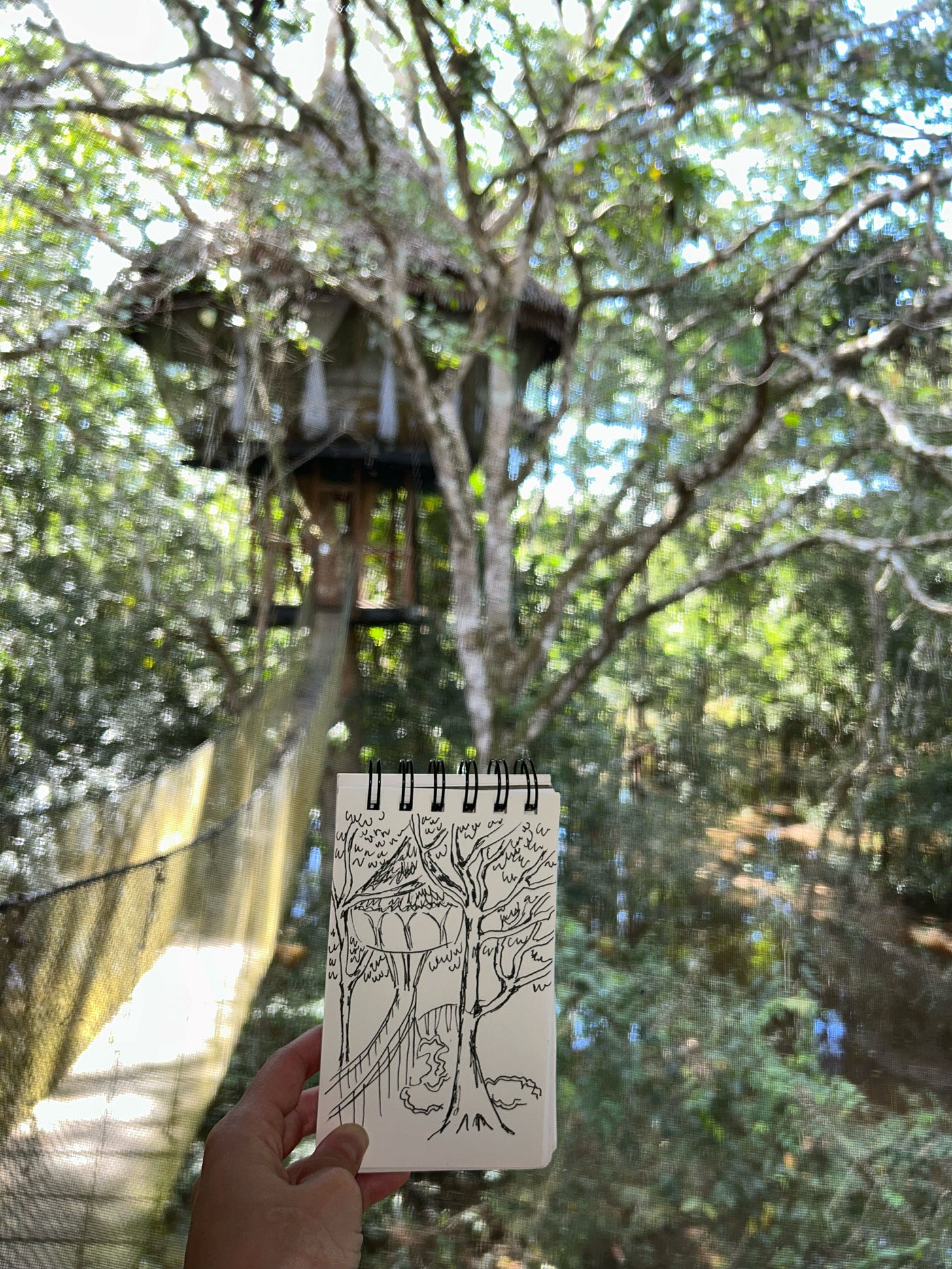

Back at the treehouse we encounter the other guests, a family of Americans led by a loud blonde lady in patterned yoga pants and chunky stone jewelry. She’s trailed by her two lumpy, androgynous children.

Every morning the blonde lady comes to tell us about what she touched the previous day—a boa constrictor, a stray dog, a sloth that’s kept as a pet by the nearby village. She shows us photos of the sloth posing with her and each of her kids. She’s breathless and excited. I wonder what she gets out of touching everything.

Our treehouse is a ten-minute walk from the boat dock, up four flights of stairs and across a precarious rope bridge. As we walk towards it I start to notice the bugs. A massive, pink-toed tarantula scuttles around us. Then, as I’m mounting the first flight of steps, I see that they’re crawling with enormous black beetles. There are hundreds—you can’t even see the wood.

Jay takes the lead. He’s brave at first, crushing the beetles underfoot, but that seems to upset them, so they start to fly. Clouds of them rise from the stairs and start hitting us, whacking our bodies and our faces, and they’re heavy, making thwacking noises when they make contact. I’m screaming my head off. Jay is also bellowing. We make it to the landing and look at each other, safe for the moment, when something heavy slams into the ground between us. A snake? We were warned about them. But when I look down it’s so much worse: A giant Amazonian cockroach. It’s the size of a rat.

Jay shouts “motherfucker!” and abandons me, running across the rope bridge, which we’re not supposed to do. I bounce after him, nearly flying right off and into the water below.

In the treehouse I wiggle around to rid myself of bugs. A few serene beetles tumble to the ground. The room is covered in netting but I’m crazy now, so I start hunting for insects. There are a few grasshoppers and I kill them like a maniac. I turn on Jay, ask him if he’s just gonna stand there or help me kill the bugs? He grabs me by the shoulders. “Sang, we’re in the Amazon, you can’t kill them all.”

I try to sleep, but the jungle comes alive at night. There are a million insect whines, but now there are other strange noises: Brown doves that sound like a pod of melancholy whales; the raptor scream of a parakeet; a wet, video game plop!, which I’m told is an oriole.

I huddle under my bathrobe because I saw a bug on my blanket. When did I get so weird about insects? I used to love them. As a child I kept spiders in jam jars, and an ugly brown cricket in a shoe box. I carried tree frogs in my pockets until they suffocated, and then I would cry for days. My only real pet as was a snake I caught in the woods behind my house. One time it escaped; I found it a week later hiding in the warm cables behind the television.

Thunder rumbles in the distance and I’m assaulted by another memory. The Rainforest Cafe. Remember that place? They were usually in shopping malls. I’d go there for my birthdays, and every thirty minutes, ‘thunder’ would crackle over the loudspeakers, the animatronic gorilla would scream, and misters on the ceiling would start to ‘rain’ on my chicken fingers.

It starts to rain now, and presently I fall asleep. I’m awakened in a cool blue dawn by the strangest noise yet: rhythmic drumming, right outside of the door. Knock, knock-knock. Knock, knock-knock. Over and over again.

I put in earplugs and go back to sleep. When I wake up the rain has stopped. Sun is streaming into the treehouse. Just above me is a humongous, hairy, pitch-black tarantula. It’s creeping shyly across the ceiling, but when I look at it stops dead like it knows it’s busted.

I think about how to kill it, but quickly suppress the urge. What would the blonde lady do? Surely she would stroke it. And Orlando? He’d probably relax and let it be a fucking spider. And eight-year-old me? She’d be thrilled to find a tarantula. She would name it something nice, like Penelope, and keep it as a pet.

April 11, 2023

Orlando says the drumming was a porcupine. I’m skeptical, but I have to trust him. He knows everything about animals. This morning he’s spotted, from a half mile away: a camouflaged iguana, a sloth swaying in a high tree, and a family of tiny bats, fast asleep on a tree trunk, completely invisible until I frightened them awake.

He can also talk to animals. Now he makes a squelching noise that coaxes from the trees a family of yellow monkeys. They have tiny babies clinging to their backs. “Aw, the bambinos!” he cries, squelching some more. They’re soon joined by a group of pygmy marmosets. They’re the smallest primates in the world, with exquisite monkey faces the size of a quarter. Then we’re approached by a pair of wooly monkeys with thick mahogany fur. Orlando produces some plantains, which they take from my hands. The gesture is so polite. Their tiny black fingers brush my palms.

The bugs aren’t so scary in the daylight. A grasshopper in flight looks like a storybook fairy, with enormous green wings and long, womanly legs. There are clouds of drunk red butterflies, and two electric blue morphos the size of birds. I’ve never seen a blue so vivid in nature and at first, I’m annoyed, mistaking them for waving bits of plastic.

We’re out looking for the snake, traveling by boat through narrow streams and mangrove forests that spill into the jungle’s primordial cul-de-sacs. Our first stop is a tranquil oxbow lake where we find a fat red bird called a hoatzin. It’s a dinosaur, explains Orlando—it has the same blue face and crested head it did 34 million years ago. The babies are born with claws on their wings like pterodactyls.

Huge, ancient trees loom over us, sinewy and elegant, ballooned here and there by termite nests. My favorites are slim and white, tufted with bright green leaves shaped like cilantro. They have squiggly branches, like a Rousseau tree—Rousseau who painted magical jungle scenes, but who never visited one, who never left France.

I wonder what he would think of the real jungle, the plastic Sprite bottles in the river, the gasoline sheen on the water, the toilet smell of the swamps. Surely he didn’t imagine the bugs, not in his tropical Edens full of naked brown Eves.

But who am I to talk? I’m worse than romantic. Me, whose understanding of Peru has been gleaned mostly via History Channel specials about aliens and the Nazca Lines, a few paragraphs on Incan blood sacrifices in a middle school textbook, and the Emperor’s New Groove, which I watched like an idiot on the plane ride from Lima.

We turn into another lake, this one covered by colossal lily pads. These are three feet wide, strong enough to carry a toddler, with thorny red bottoms to skewer hungry fish. I’m leaning over to examine one when two winged, black beasts fly over us, baying like sea lions. They blot out the sun. I squeal in fright. “That’s a dinosaur,” says Jay, ducking. “Actually they are vegetarians,” says Orlando, dryly. “Horned screamers.” He bays at the birds who make gleeful honking noises back at him.

On our way home Orlando plucks some orchids off of a tree and hands them to me, says to take them back to the lodge and put them in some water. A few moments later, a long, spindly branch from the same tree scoops off his hat, lifting it into the air. Another branch knocks my Prada glasses off, and a third slaps Jay in the face.

“It’s because we took the flowers,” says Orlando, chuckling. A troupe of birds cackles in response. “See,” he says, “they’re laughing at us too.”

Postscript

On transportation and lodging: We stayed at Treehouse Lodge. It’s a solar-powered ecolodge set between several nature reserves. The staff, food, and accommodations are all wonderful. I recommend treehouse ten, which has a good view of the river, and where we lived after the tarantula moved in.

The lodge is a three-hour journey by road and boat from Iquitos, which is a 2-hour flight from Lima (Iquitos is deep in the jungle and inaccessible by road.) Travel sites describe Iquitos as a sophisticated jungle riviera with elegant boulevards and riverside restaurants, which is maybe what it was during the late 19th-century rubber boom. Its prosperous past is evident in the few stained, European-style churches (and a metal villa rumored to have been designed by Gustave Eiffel) but today, it’s a kind of bustling shanty marked by ramshackle, tin-roofed buildings.

We stayed a night in the nicest hotel in town, a DoubleTree, where I pounded warm Fernet and cokes and indulged in the fantasy that I was an ex-pat hiding from the law.

On guides: You can’t go into the rainforest without one. Orlando is the best. He does customized trips. You can look into it here.

On bugs and vaccinations: You only really need to worry about mosquitos. I carried malaria medication but there is no need, as it’s not endemic in the area. Same with yellow fever, which I didn’t get vaccinated for (get typhoid and tetanus.) I got a few bites but they were small and not so itchy. Still, bring hydrocortisone, wear light, long-sleeve clothing, and use bug spray with DEET.

Read next: How to say 'enema' in Spanish? A long weekend in Mendoza, Argentina's high-altitude wine country.